Censorship in the United States

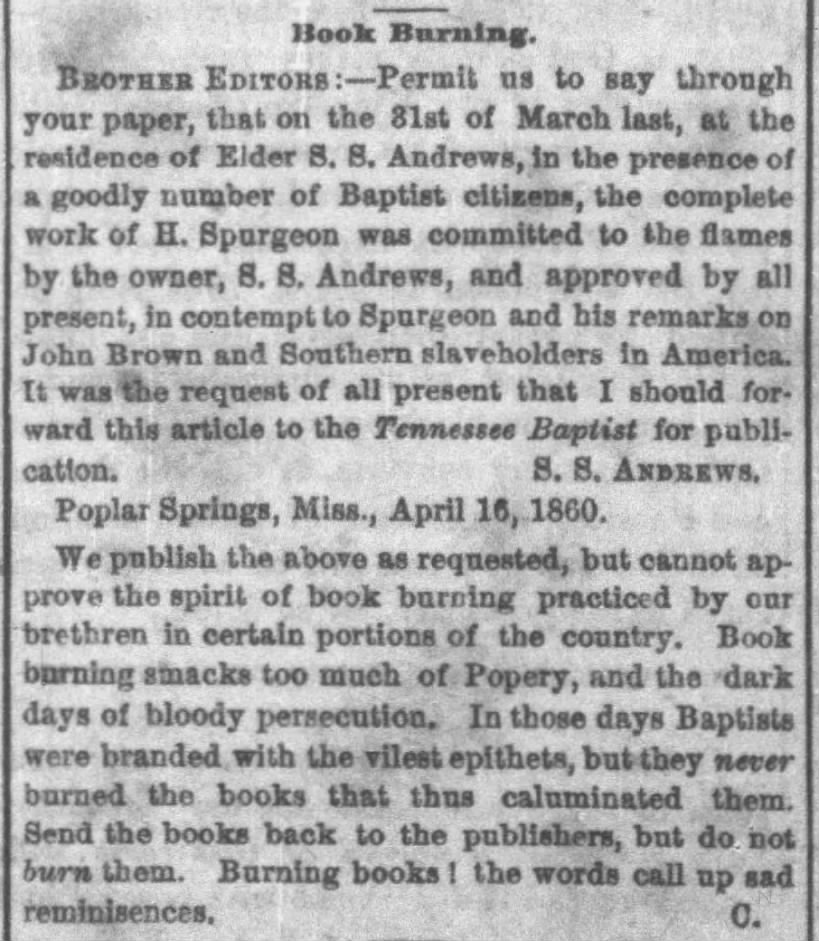

On March 31, 1860 there was a book burning at the home of S. S. Andrews, an Elder in the Baptist Church in Poplar Springs, Mississippi. During this night, Mr. Andrews and “a number of Baptist citizens” proceeded to burn the works of Charles Spurgeon, a minister who spoke out through journalism against the Institution of Slavery.

So proud of their burning were they that Mr. Andrews, himself, wrote a letter to the editors of Baptist newspaper publications to report it. Here is his notice, which includes a note from the editor that expresses disapproval of book burning.

Charles Spurgeon, whose works they burned, was an esteemed pastor in England. Beginning in 1860, a Boston newspaper called the Christian Watchman and Reflector published several letters from Spurgeon as a correspondent.

In these letters, in order to dispute claims that he was tip-toeing around the subject of slavery in order to stay in the good graces of his Southern U.S. readers, Spurgeon addressed the subject head-on with a blistering disapproval of the institution. He also professed his admiration of John Brown, the militant abolitionist who was hung to death for his instigation of a revolt of enslaved people at Harpers Ferry, which many consider to be the precursor to the U.S. Civil War. (You can read all of Charles Spurgeon’s letters here.)

He said, “Having no slaveholders in England, I should have been beating the air if I had preached against slavery to my people, for this is the very last crime they are likely to commit. It is far more probable that any slaveholder who should show himself in our neighborhood would get a mark which he would carry to his grave, if it did not carry him there.” It was with words such as these, written on January 26, 1860, that Charles Spurgeon ignited the book-burning response of these Mississippi residents.

Book burning has been seen as a way to control information and the historical narrative going forward. In no way a novel idea, it’s rather an action common to those seeking to maintain control of the hearts and minds of people. Historically, those leading the charge were emperors and popes desiring to establish themselves as the first or the one and only. One of the most notorious examples, of course, is when the Nazis sympathizers in Germany, on May 10, 1933 gathered in Berlin to hold a massive book burning.

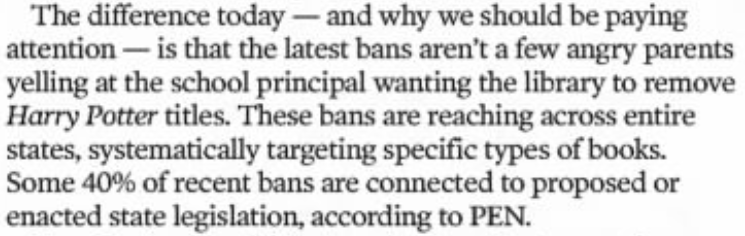

One difference to note in the history of U.S. book bans or burns is that the government has never led something of this nature, as in the historical examples of China and Germany. In our experience, it’s been fellow citizens leading the charge. Citizens wanting to censor other citizens is an entirely different scenario than a government or conquering ideological entity imposing a ban on existing knowledge. In our case, it’s religious zealots who spin a narrative that we are a nation founded in their image, rather than a melting pot where religious freedom is paramount, and in doing research, one finds they are always in the minority. Every time the notion of book-banning rears its head, there is a wash of backlash in the media and very little actual burning of books. Though, it is noteworthy that in the current instance it seems to come with an added threat of corresponding legislation.

We live in a digital age where any sort of burning is definitely only symbolic. In past times people often noted that burning books does not erase ideas or thought. That most certainly holds true today. So even though there is a more poignant effort to involve the U.S. government in censorship, including a continued effort to censor what our youngest citizens can learn, it will be impossible to contain the vast knowledge available to everyone at any instant. However, the image it conjures at the mere threat is powerful. It creates division and fans hatred.

In 2023, there are more “banned” books in the United States than ever before.

On a positive note, these attempts serve as an unintended catalyst for people seeking new reading material and each time it makes the news, the sale of “banned” books increases. Books may be banned from school libraries and sometimes public libraries, but it is not possible to ban them from the internet or book stores. (Anyone can get a New York Public Library card and access free content.) For more information about the current state of citizen-led censorship in the U.S., you can visit The American Library Association, which has complied a list of books that have been challenged over the past three decades. They are also credited with the creation and promotion of the annual Banned Books Week. For book bans prior to this compilation, a search of old newspapers is helpful.

News and Record Greensboro, North Carolina Sunday, February 12, 1956

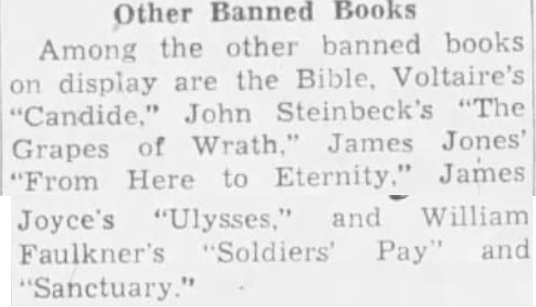

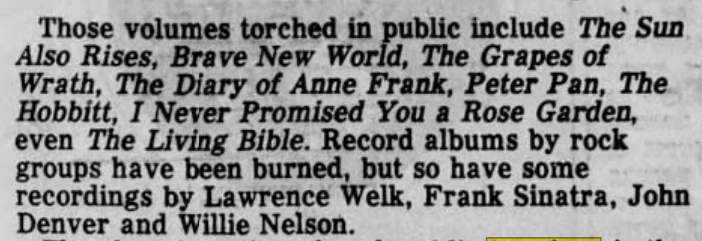

Below you’ll find a collection of newspaper articles about book burning or banning throughout U.S. history:

Found this page from a 🧵response you left and am glad I took the time to read it. Thank you for the history class and resources