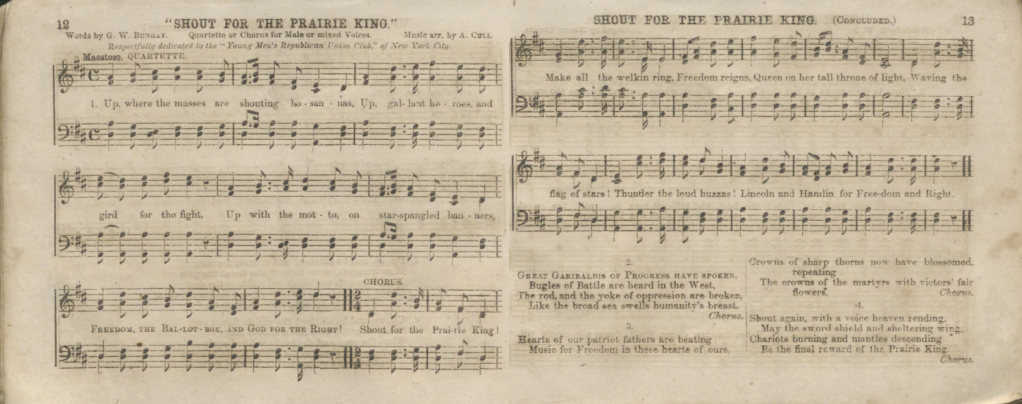

“…Lincoln and Hamlin for Free-dom and Right!” They sang as they marched in the Northern streets during the time leading up to the 1860 presidential election. The Wide Awakes were a group that supported the Party of Lincoln, whom they dubbed “The Prairie King.” Lincoln was the Republican candidate, and at that time the Republicans stood for equality, freedom, free-market, and were champions of the common man. They were the party of the people.

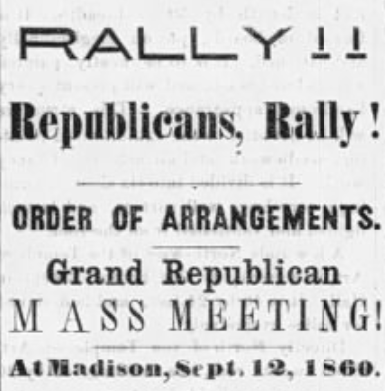

The Wide Awakes were officially formed in Hartford, Connecticut in the years prior to the 1860 presidential election. By the time the election was in full-swing, the Wide Awakes bragged of having chapters in every Northern town. This group championed anti-slavery and consisted of younger people who were proud to be “wide awake” compared to older men. They wanted to make the voices of the young people heard and they aimed to get them riled up to vote. So, they created a movement, primarily at night while the older men were already home in bed.

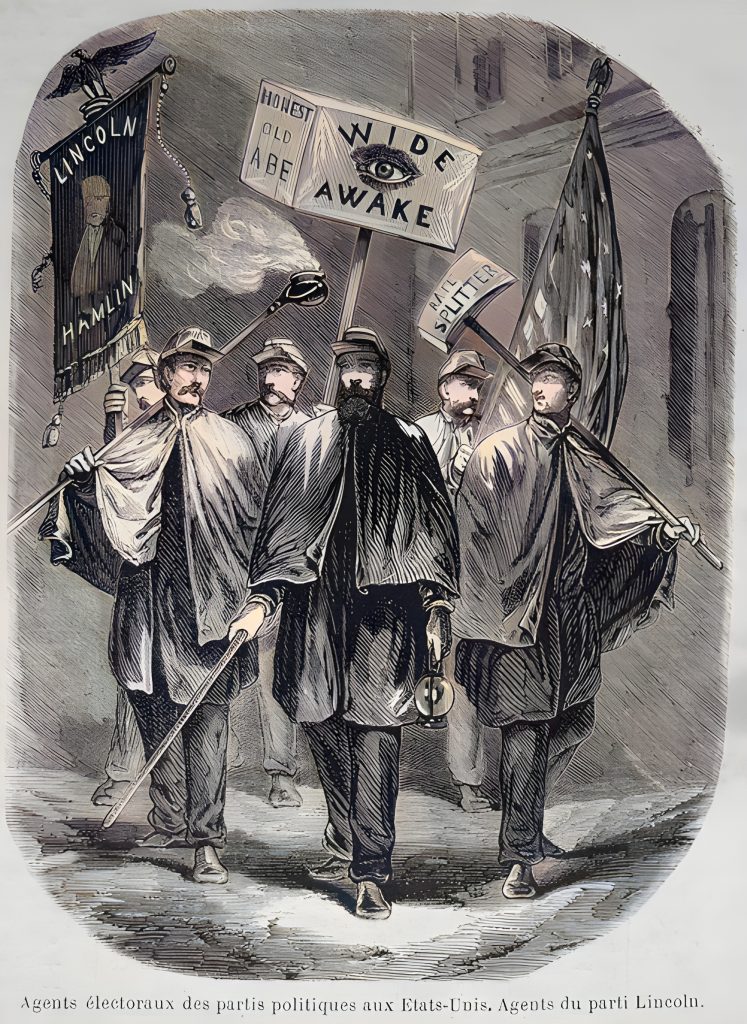

As you might think, the North and the South had different perceptions of the Wide Awakes. To those in the North, the young men were rallying the voters by being boisterous and attempting to enlighten the common man with their torches and lanterns. To those in the South, these were bands of men marching, carrying torches, while claiming to be ready to fight.

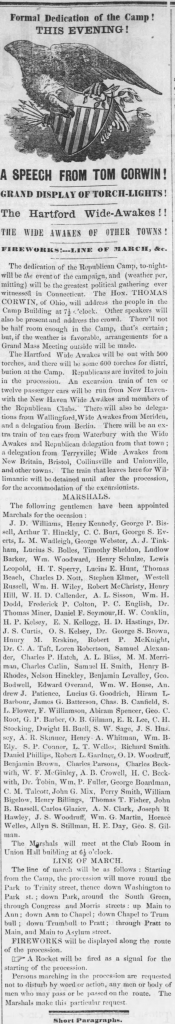

The men of these freedom clubs did, in fact, march by rank. The glass of their lanterns were colored according to rank. They were not small outfits – but rather 500 men marching and singing while thousands of spectators looked on. They were a large political movement that was most intently focused on getting their candidate into office through awareness, not violence.

The 1860 United States presidential election featured four major candidates from different political parties. The election was significant because it took place on the brink of the Civil War. At that time, the Republicans supported the complete abolition of slavery, but especially did not support the expansion of slavery into American territories. The Democrats either outright supported the Slave Code (slavery was a permanent condition) or held that it was the right of states, especially newly formed states, to determine whether or not their system would include slavery. (Though the names of the political parties of the 1860’s may confuse people today, suffice it to say that after the Civil War and over the course of the decades leading up to the Civil Rights movement and the Southern Strategy of the 1960’s, the two main political parties have essentially switched ideologies regarding their support of people versus industry.) In 1860, the candidates were:

- Abraham Lincoln (Republican Party):

- Lincoln, a former Illinois congressman and a self-taught lawyer, became the Republican Party’s nominee. He was an outspoken opponent of the expansion of slavery into the new territories.

- Stephen A. Douglas (Northern Democratic Party):

- Douglas, a U.S. Senator from Illinois, was nominated by the Northern faction of the Democratic Party. He was a key figure in the debates over the issue of slavery in the territories and is best known for the Lincoln-Douglas debates.

- John C. Breckinridge (Southern Democratic Party):

- Breckinridge, the sitting Vice President and a U.S. Senator from Kentucky, was nominated by the Southern faction of the Democratic Party. He advocated for the protection of slavery and states’ rights.

- John Bell (Constitutional Union Party):

- Bell, a former U.S. Senator from Tennessee, was the nominee of the Constitutional Union Party, a short-lived party that aimed to avoid the divisive issue of slavery. The party sought to preserve the Union by emphasizing Constitutional principles.

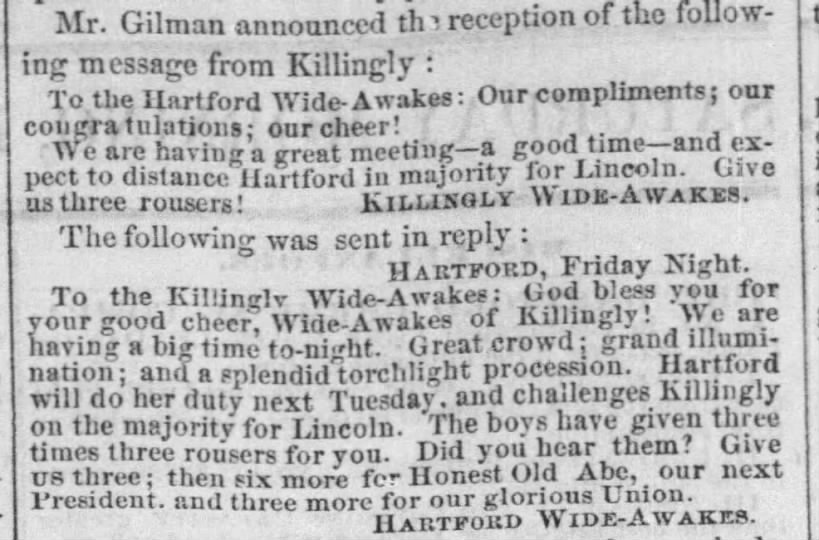

The Wide Awakes also served as a type of self-appointed “political police” who aimed to protect their presidential candidate and bring awareness and “light” to the people. They wrote songs, created signs, marched with lanterns and oil cloth capes that protected them from the drippings of their torch-lit parades. Rallies and other public events were arranged to generate enthusiasm, to enlighten people, and to advocate for the abolition of slavery. Their distinctive uniforms and torch-lit processions were meant to capture attention and create a sense of unity among their supporters. Their movement was raucous and even once was thought to be the source of a shaking that was in actuality caused by a small earthquake.

07 Sep 1860, Fri ·Page 1

Though men were the primary marchers, women who supported the cause were credited with hospitality and helping to facilitate the marches and gatherings. There were ladies’ galleries where the women would gather to watch to parades.

The president of the original Hartford group was George S. Gilman, Esq. On November 3, 1860, a few days before the election, he gave a resounding introduction to William M. Grosvenor, Esq., who was a contributor for the New Haven Palladium newspaper. A summary of Mr. Grosvenor’s philosophy follows:

Ultimately, Abraham Lincoln won the election, becoming the 16th President of the United States. His victory prompted several Southern states to secede from the Union, leading to the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861.

While the Wide Awakes were primarily associated with the 1860 election, their brief existence is remembered as part of the political and social history of the United States during a pivotal time leading up to the Civil War. After Lincoln won the election, the Wide Awakes remained active for a couple of decades, though less fervently. (Today there are re-enactors and even a resurgence.)

Your passion for this topic is contagious! After reading your blog post, I can’t wait to learn more.

I’ve never commented on a blog post before, but I couldn’t resist after reading yours. It was just too good not to!

Your blog post was like a crash course in [topic]. I feel like I learned more in five minutes than I have in months of studying.

Your blog post was the highlight of my day. Thank you for brightening my inbox with your thoughtful insights.

Your blog post was the highlight of my day. Thank you for brightening my inbox with your thoughtful insights.

Your blog post is incredibly insightful and well-written. I found myself nodding along with every point you made. Keep up the fantastic work!

Your writing is so clear and concise! The way you explained everything step-by-step helped me understand a topic I previously found confusing. Great job!

Your blog post was like a breath of fresh air. Thank you for reminding me to slow down and appreciate the beauty of life.

This is the kind of detailed content I love to read. I appreciate how well you explained every aspect of the topic without making it too complicated.

Your blog post was like a warm hug on a cold day. Thank you for spreading positivity and kindness through your words.

Each line feels like a stepping stone, leading the reader toward greater understanding and insight.